This video on war picture books is not identical to this article, but provides additional visual information.

What are war picture books?

Children’s and teenage literature is written and illustrated by adults for children, with the result that circumstances which shape adult life at a certain time in a certain place can naturally find their way into children’s literature. Since war strongly shaped the world view of authors and the way of living of whole societies in certain parts of history, war became a part of picture books as well.

But picture books haven’t been around forever, they are fairly new in comparison to the history of literature. This has different reasons. Roughly speaking, in western countries children were treated like little adults until the late 19th century. This changed with the popularity of progressive education, which focused on educating children from their point of view, instead of the adult’s view of the world. Added to that, technology advanced rapidly during the Victorian era bringing printing costs down and making picture books a viable business option. Early picture books like those of Walter Crane (1845-1915) or Randolph Caldecott (1846-86) paved the way for what we know to be picture books today. (Meggs / Alston 2012: 168) Since then, the medium and its content has developed alongside history, including the first and second world war. This article will focus on these two wars and what picture books in Europe and especially in Germany represented.

Picture Books during the 1st World War

Picture books on the topic of soldiers and the military were created and sold not only during but also before the First World War. In the period between the founding of the German Empire in 1871 and the First World War, the military and war were unavoidable subjects, primarily due to the previous devastating conflict with France and the tensions that persisted after. Picture books often addressed soldiery as a profession of choice and were aimed primarily at boys. The books focused on depicting the soldier’s occupation and the soldier’s life as honourable and desirable. Additionally, they could mentally prepare boys for compulsory military service they would have to face in their late teen years. The First World War began in 1914. The enthusiasm for it was still relatively high, supported in part by the early confrontation with the topic in children’s literature. (Lukasch 2012: 151) War picture books were used in order to explain and justify the war to children. Often their fathers left only to never return, or many who did were seriously injured. Picture book illustrations varied strongly in their suitability for children, ranging from inappropriate to extremely euphemistic. (Lukasch 2012: 158) The picture book “Wir spielen Weltkrieg” (We’re playing World War) is an example for such a positive representation of the topic. It was created by the illustrator Ernst Kutzer and the author Armin Brunner in 1915. The humorous picture book shows children playing war in a child’s bedroom. Here is a passage from the book, in an English translation by me, without rhymed verses (German original text can be found at the end of the article):

“In the trenches we’re well covered,

Only the barrel pointing out.

Aim! Open fire! Those with red trousers,

The ones tumbling down, those are the French!”

(translated from Lukasch 2012: 162)

The pictures show children hiding under a couch, pointing guns at toy figures. Another picture book tried to explain how the war came about in a style seemingly suitable for children. “Lieb Vaterland magst ruhig sein!” (Beloved fatherland be unconcerned!) was created in 1914 by Arpad Schmidhammer. Here children are representatives of nations and fight side by side or against each other. It starts with these verses:

“Michl and Seppl are peacefully

Maintaining their flower garden.

This angers in the neighbour’s house

Lausewitsch and Nikolaus.”

(translated from Schmidhammer 1914)

Seppl represents Austria-Hungary, Michl stands for the German Empire, Lausewitsch for Serbia and Nikolaus for Russia. Later Jacques as France, John as Great Britain and a monkey as Japan join them. Partly dressed in uniform, the peaceful garden scene develops into a mass brawl. When finally Michl and Seppl are victorious they lock up their enemies. Schmidhammer created other picture books with the same characters, which, however, were even less suitable for children. These include “Maledetto Katzelmacker” (Katzelmacher: A derisive Austrian/Bavarian term for an Italian) in which Italy’s role as an opponent of the German Empire and Austria-Hungary was addressed and “John Bull Nimmersatt” (John Bull the glutton) in which England was again brutally fought by the Germans. (Lukasch 2012: 163 ff.)

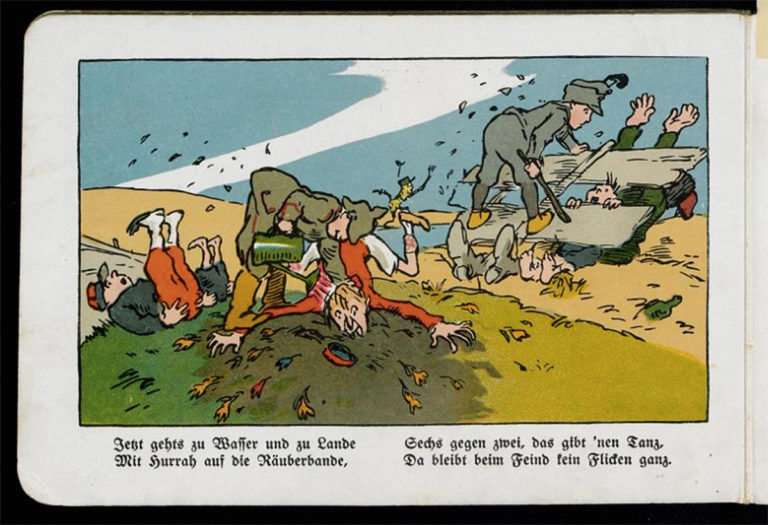

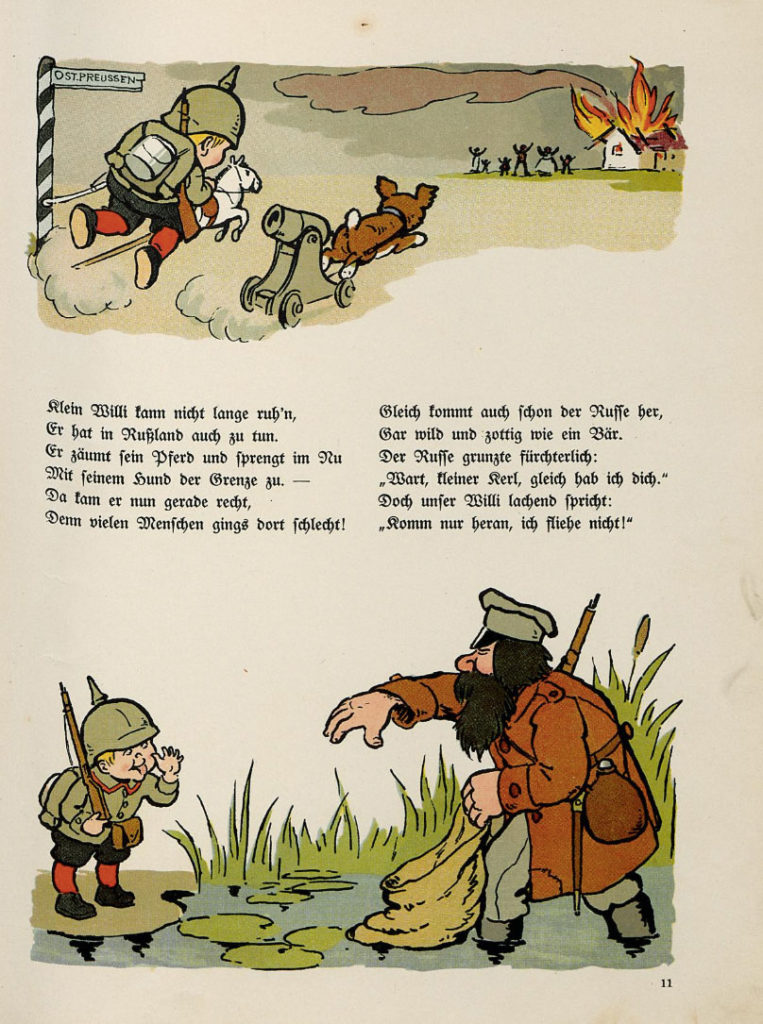

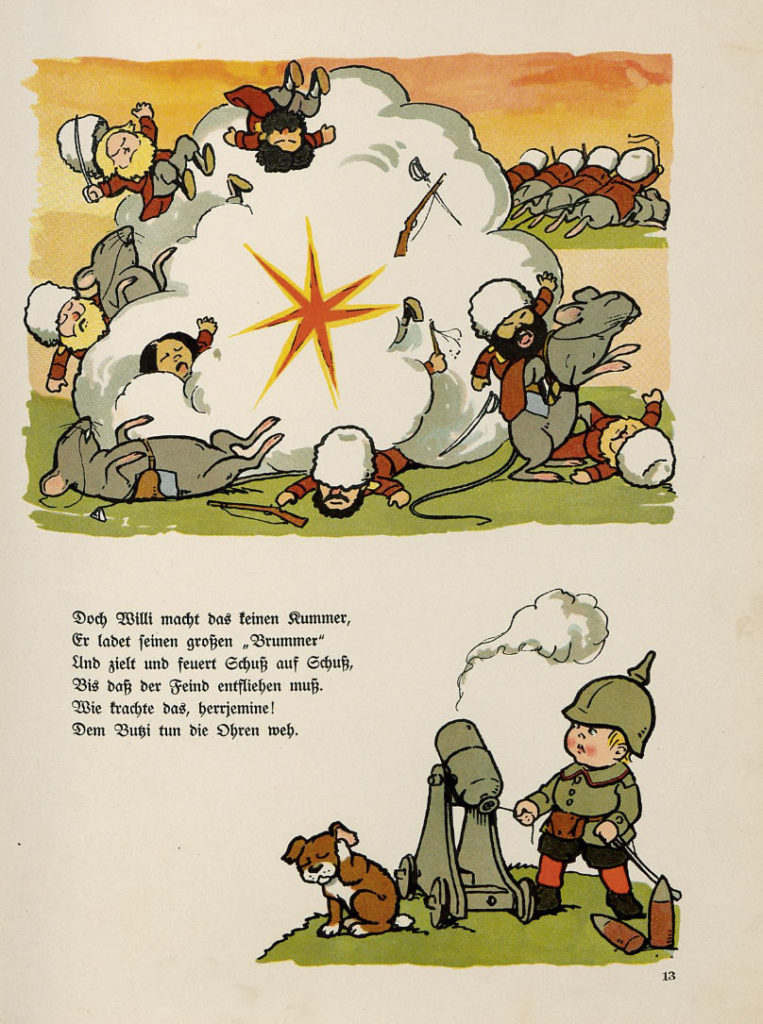

Another more professionally illustrated picture book from the time was “Hurra!” by the Swiss author and illustrator Herbert Rikli. He also used the idea of children representing nations in war. Rikli created this dangerously cute war picture book while working in the German Empire, but after returning to neutral Switzerland shortly after the war started, he went on to writing “normal” children’s books. (Lukasch 2012: 167 f.) In it a boy called Willi hears of stories from the war and goes on to dream about shooting and killing Russians and Frenchmen. Later in his dream he meets Franzl, who stands for Austria-Hungary, and they fight their enemies together. After being injured by grenades they are treated in a cosy military hospital. Now healed Willi attacks his enemies in a submarine and Zeppelin before he and Franzl are victoriously celebrated. Finally, Willi wakes up from his dream wishing for it to have been real. (Rikli 1915) The imaginative scenes are skilfully illustrated, colourful and childish and the war is literally presented as something to dream of. The figures shown here have child-like characteristics, big heads and small bodies. This makes them look sweet and they become immediately likeable. This is a common practice which is used throughout children’s entertainment and can be seen in picture books, comics as well as animated movies. The dog as a loyal friend and companion supports the main character, so Willi never seems lost or lonely in this unknown dream world. This kind of presentation of the war as a funny adventure created unrealistic images for children. The picture book not only justified the war, it also aimed to spread enthusiasm.

Pages from “Hurra!” by Herbert Rikli

Other picture books like “Lustiges Kriegsbilderbuch” (Fun War Picture Book) by Ernst Kutzer and Adolf Holst as well as the beautifully illustrated work “Heil und Sieg!” (Salvation and Victory) by Marie Flatscher and Ludwig Morgenstern work in very similar ways. The examples given above are directed at a very young audience. War Picture books for older children additionally presented the war outside the children’s bedroom, depicting soldiers and their seemingly honourable combat operations. (Lukasch 2012: 170ff)

The aim of war picture books was to justify the war, to discredit the enemies and to strengthen the support of the people. Such books weren’t just published in Austria-Hungary and the German Empire, the First World War was the subject of many picture books world-wide. Especially children in France were not spared from war propaganda and had a large selection of magazines for children and adolescence to choose from, which illustrated the war in similar ways as the picture books did. These were of course especially hateful towards Germans, probably not only because of the war at the time, but also the memory of the Franco-German war in 1870/71 (Lukasch 2012: 185 ff.).

Picture Books during the 2nd World War

During World War II there were significantly fewer war picture books published and hardly any were comparable in artistic quality to the one’s created during the First World War. Illustrated books that conveyed Nazi ideology were largely confined to school textbooks, while younger children were hardly touched by political propaganda in children’s print media at all. The fact that picture books found much less popularity in the Third Reich can have different reasons. Firstly, not many professional book illustrators were available for propaganda purposes. Deviating political ideals between artists and government as well as the expulsion of artists by the Nazi regime might have contributed. Secondly, war coverage was strictly monitored by the state, which made a humorous and creative approach to the subject (as during in the First World War) rather improbable. Thirdly, the demand for children’s literature about war presumably wasn’t very high among the population, because unlike during the First World War the enthusiasm for war was rather low. (Lukasch 2012: 285 f.)

Only a few war picture books were created by well-known illustrators. One example is “Mit Säbel und Gewehr” (With Sword and Rifle) which was illustrated by Fritz Koch-Gotha, who was known for the rather harmless picture book “Die Häschenschule” (A Day at Bunny School). This war picture book is similar to those from the First World War and again addresses the war by children playing soldiers. Another well-known illustrator at the time was Herbert Rothgaengel, who provided illustrations to other picture books of that kind. War picture books of the Second World War seemed much more serious than those of the First World War. They were less light, cute and humorous. (Lukasch 2012: 286 ff.) Jokes and laughter could be found in American publications, which started mocking the Nazi regime very early on, even before America entered into war. This coincided with the rise of superheroes such as Superman, which became a huge success and caused several other superheroes to emerge. The fight against America’s enemies was nutritious ground for the superhero genre and with it the art of the comic book. (Lukasch 2012: 295 ff.)

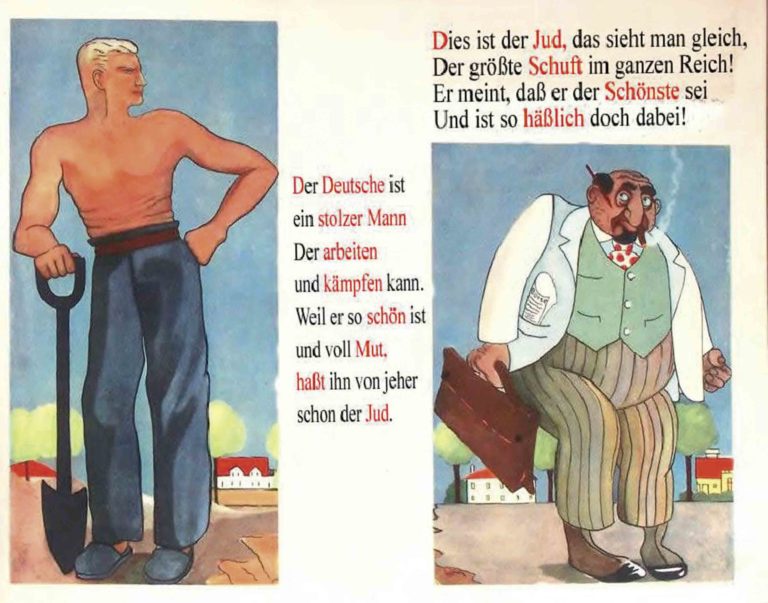

Aside from war picture books, there were also hardly any other picture books with clear ideological messages along the lines of National Socialism. In Germany illustrated children’s literature at the time mainly focused on harmless and neutral picture books, with stories and messages which wouldn’t come into conflict with the government’s value system. (Lukasch 2012: 311 ff.) This way, Nazi ideology could hardly be found in the picture books themselves, but rather in the absence of conflicting values. The stories simply didn’t contain any Jews or other concepts of enemies created by the National Socialist German Worker’s Party (Nazi Party). Exceptions were three books by the publisher Stürmer, which set out to propagate National Socialist ideas. “Trau keinem Fuchs auf grüner Heid und keinem Jud bei seinem Eid!” (Don’t trust a fox on green heath and no Jew at his oath!), “Der Giftpilz (The toadstool) and “Der Pudelmopsdackelpinscher” (The Poodle-Pug-Dachshund-Pinscher) were aimed specifically against Jews and wanted to give people biased information on their alleged characteristics. Of those three books only the first one can be described as a picture book in the traditional sense of the word and was aimed specifically at small children. The other two books were much more text heavy and had fewer illustrations. (Lukasch 2012: 309ff)

Picture Books and their Messages

War picture books are characterized mainly by their content, they embellished war at wartimes for children and let them dream of a glorious soldier’s life. The picture book “Hurra!” by Herbert Rikli is probably the best example for such manipulation. While war picture books might be an extreme example, it does show that the medium of picture books can provide more than just entertainment. Ideological messages like those of war picture books (especially from the First World War) can have a strong impact on the way children perceive their world. While it is understandable, that mothers would hand stories of soldiers to their children when their father went to war, the messages in books like these can do at least as much harm as they can give comfort.

Original German text passages

„Im Schützengraben sind wir gut gedeckt,

Nur der Gewehrlauf wird hervorgestreckt.

Setzt an! Gebt Feuer! Die mit den roten Hosen,

Die jetzt dort purzeln, das sind die Franzosen!“

(Brunner quoted from Lukasch 2012: 162)

„Der Michl und der Seppl warten

Ganz friedlich ihren Blumengarten.

Das ärgert aus dem Nachbarhaus

Den Lausewitsch und Nikolaus.“

(Schmidhammer 1914)

Sources

Lukasch, Peter (2012): Der muss haben ein Gewehr. Krieg, Militarismus und patriotische Erziehung in Kindermedien. Norderstedt: Books on Demand.

– Find on Amazon: https://amzn.to/2AKjUYV

Meggs, Philip B. / Purvis, Alston W. (20125): Meggs’ history of graphic design. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

Rikli, Herbert (1915): Hurra! Ein Kriegs-Bilderbuch. In: http://digital.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/werkansicht?PPN=PPN735280886&PHYSID=PHYS_0001&DMDID=, accessed 17.12.18

Schmidhammer, Arpad (1914): Lieb Vaterland magst ruhig sein! Ein Kriegsbilderbuch mit Knüttelversen. In: http://digital.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/werkansicht?PPN=PPN73207312X&PHYSID=PHYS_0001&DMDID=, accessed 17.12.2018

One Response