A Scary Place

Jon Klassen’s picture book “This Is Not My Hat” is hilarious, and scary. How many children’s books attempt to put a thief, an alleged murderer and a liar in a picture book? And then go on to win internationally acclaimed prices?

Klassen’s book is scary, and it is scary in different ways. Firstly, the main character is presumably murdered, which is hardly ever an uplifting plot line. Secondly, it gets you to side with a thief, making you cheer on his criminal actions. Thirdly, this book is seemingly for children, and there’s not one positive role model in it.

But let’s start at the beginning. What is the picture book about?

A small fish steals a hat from a big fish but the big fish wakes up and follows the thief. A crab sees the small fish and promises not to tell anyone where he went, but does so anyway. Therefore, the big fish can find and presumably kill the small fish in order to get his hat back.

Fishy Behaviour: Actions vs. Values

So, what ‘s the message, if there is one?

As stated above there are no positive role models in this book. Therefore, looking for a hero is an impossible task. The characters personalities seem to be as follows:

- The small fish is a greedy anti-hero. His greed undermines his ability to live up to his values. He does stay likeable throughout the story but his actions become increasingly unjustifiable.

- The big fish is a supposed villain who becomes a victim. This process doesn’t change his personality nor his behaviour but it does justify his actions, at least from his perspective.

- The crab is a naive bystander, denying his moral obligations to be involved in the conflict. By trying to please everyone he becomes an active part in the persecution of the small fish.

The story does contain moral guidelines, it presents a clear line between what is morally acceptable or unacceptable. The small fish even explains: “I know it’s wrong to steal a hat. I know it does not belong to me. But I am going to keep it.” Justifying this with: “It was too small for him anyway. It fits me just right.” (Klassen 2012) The morally correct line of thoughts is stated in this text passage but the small fish decided to not act accordingly.

The picture book touches on a few deep-seated topics: Taking responsibility for one’s actions, self-control over emotional impulses and personal growth by living up to one’s values, just to name a few. It presents us with a story of how not to act. One message certainly is: “You shall not steal”, as it is written in the ten commandments. Not to compare “This Is Not My Hat” to the bible, but it does have a similar message: Stealing is morally wrong (and there’s a high chance you will get caught, and maybe killed for your crimes). But Jon Klassen goes a step further than just stating a human convention. Maybe unintentionally he asks us to do what we know to be right. Or in other words, our actions should reflect our values. Doing what one knows to be right can be hard, even for adults. And it’s even harder for a child, which is only just learning about what’s right and wrong in social situations. If the small fish had just followed his own moral guidelines his story could have ended in a more desirable manner.

Now that we know what the small fish should have done, what can we learn from the big fish? The big fish is a quite neutral character until one action defines him as the villain. Before judging to harshly, we never actually see how the story ends for the small fish. We can only assume the big fish is a murderer. Telling children, “he only stole it back from him”, might help, but even that little white lie is the wrong message to convey. If socially correct behaviour is one’s only concern calling the authorities on the small fish would have been the right move to make. This would strip the story from everything that makes it fun and engaging. Nobody would want a story like that, but it does show that the big fish is not in the right when taking justice into his own fins.

The crab is obviously not responsible for the whole situation, but he is, unwillingly, the character with the most power over the small fish. And he doesn’t live up to his values either. First, he becomes an accomplice to the small fish by promising not to tell anyone where he went. Then he breaks his promise in the blink of an eye deciding the fate of the thief. He hardly had a chance of staying a neutral bystander, not even agreeing to every request asked from him helped his case. The crab got himself into a moral dilemma. Tell the truth and potentially kill the small fish, or lie and help out a criminal. Here the message is again, do what you know to be right, and in this case, don’t promise to help a criminal. But it might be a little more complicated than that. In their discussion of the book, Caroline von Klemperer and Andy Rodgers ask the question: “Should you lie to a bully who is asking you where the kid is that they want to beat up?” (Von Klemperer/Rodgers 2016) Assuming the little fish wasn’t a thief, and/or the crab is aware of the severity of the big fish’s plan, is there a right or wrong way to act? The crab unwillingly becomes a judge in this situation.

What To Make Of It

It goes without saying that the long chain of stupid behaviour in this story is hilarious. There is something wrong in every decision any character makes. It is entertaining, true to real life and very harsh at the same time, making it more difficult to find out what to take from the story (other than a good laugh and a shocked giggle).

Does the book work as a moral compass for children? No. Not, if it’s up to children to interpret it themselves. The book can be read in many different ways, one of which being, “if you steal, don’t get caught.” Another one could be “don’t trust a stranger.” While these are reasonable interpretations of the story, they are too superficial, they don’t go back far enough in the small fish’s chain of actions. The small fish finds himself in the situation he is in not because he let himself get caught, or because he trusted the crab. He’s in that situation, because he chose to ignore what he knew to be right and stole the big fish’s hat. If a child should learn from this book, this kind of interpretation has to be pointed out to it. The story might seem simple (which is true to a certain extent, it isn’t that hard to follow the plot) but putting a thief, an alleged murderer, and a liar in a picture book does raise more questions than a typical bedtime story. These questions can be answered but children will need a little help doing so. Stories like “This Is Not My Hat” can tell us and our children more about human behaviour and social intelligence than most published novels or films even attempt

Illustrating Symbols

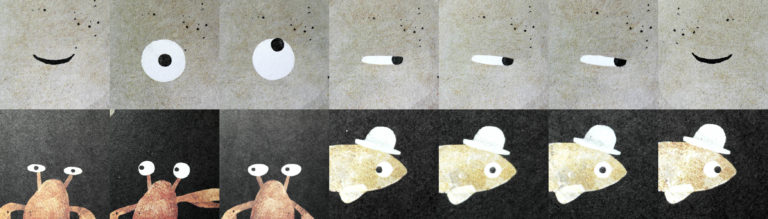

Jon Klassen’s style of illustration focuses heavily on clear, simple, flat shapes with the addition of a naturalistic look to them. This simplicity paves the way for a reading experience without distractions, neither by the text nor by illustrations. It focuses all the attention on the story, no flashy art style, no poetic word-games, the story is the centre of attention. This heightens the quality of the reading experience since the style matches the straight forward and painfully relatable behaviour of the characters. Klassen limits himself to very basic possibilities of expression. Both the small fish and the big fish have only one way of expressing their feelings, their eye (singular).

In regard to facial expressions, Klassen explained: “It doesn’t have to look very complicated. It’s a symbol of how they’re feeling.” (Art of the Picture Book 2014) This comment can be related to his style over all. Talking about trees in the same interview with “Art of the Picture Book”, he noted:

“You are up against your own skills as an artist. You can only play at making a fake tree. No one thinks it’s a real tree, but they know it’s supposed to be a tree. That’s way more fun than actually trying to draw a tree.”

Jon Klassen (in Art of the Picture Book 2014)

Klassen doesn’t try to create a real world in his picture books, he creates symbols which refer to the real world. By doing so, the viewer creates the degree of reality in his or her own mind. Klassen doesn’t have to, nor wants to trick anyone into an illusion of reality. While the fish communicate their feelings purely through their eyes the crab is a bit more flexible. But even here, Klassen doesn’t really take much advantage of the crab’s limbs or the possibility of him interacting with his surroundings (by eg. hiding). In the contrary: Singling in on it, the crab’s feelings aren’t very obvious at all even when showing the big fish the way. His feelings only become obvious taking the eye of the big fish into account. If the big fish were happy, the crab would seem happier too. The circumstances strongly influence the viewers perception of the feelings, not necessarily the characters by themselves.

If the illustrations are more or less just a chain of symbols relating to each other, how can we define the quality of illustrations? Illustrations don’t have to be detailed, naturalistic, colourful, or any other attribute one could list. The art style is arbitrary. There are styles which go better with the content of a book than others would, but that doesn’t make the illustrations themselves better or worse. When matching content to a style of illustration, author and illustrator Tom Lichtenheld says: “If a story is soft and lyrical, I’ll use watercolours or pastels, but if it’s gritty, like Goodnight, Goodnight, Construction Site, I’ll use crayon on textured paper.” (quoted from Hana Hladíková 2014: 22)

The illustrator tells a story, which is where the quality lies. The symbols Klassen mentions can be a strong indicator for quality. Good illustration is less about technical refinement and more about decisions illustrators make. What should be shown? What can be left out? Which visual elements are able to tell the story most effectively? Or can aspects be added which contribute to the feeling of the story? There is a reason for every visual element in “This Is Not My Hat”. Besides some aspects of design (eg. the use of contrasts and composition) this kind of thought-out and carefully built chain of symbols makes the difference between visual reduction and poor-quality illustrations.

When Text and Images Collide

Picture books are more complex, than just good text and good illustrations. Both elements are crucial by themselves and need to work together as well. First, let’s cover the basics.

There are different ways of defining the relationship between text and images in picture books. Both, the written text and the images tell a story together, but usually in slightly different ways. Illustrator and author Maurice Sendak (Where the Wild Things Are) explained:

“You must never illustrate exactly what is written. You must find a space in the text so that pictures can do the work. Then you must let the words take over where words do it best. There’s an interchangeability between them, and they each tell two stories at the same time.”

(quoted from Lanes 1980: 110)

Jens Thiele, a German researcher on children’s literature, defines three categories of relationships between text and images. I’ll suggest an English translation here, since I couldn’t find an existing one.

- Parallelism of image and text (Parallelität von Bild und Text)

- Plaited braid (Geflochtener Zopf)

- Contrapuntal tension (Kontrapunktische Spannung)

In the first case images and text tell the same or a pretty similar story. They might each add information if some is missing. The second category covers cases, in which image and text each add their own unique aspects to a storyline while still following the same plot. In the third category, images and text increasingly oppose each other, to the extent of contradicting what one or the other communicates. (Thiele 2003: 75) Another categorisation was popularized by researchers Nikolajeva and Scott who identify five different categories instead of three. They use “Counterpoint” as this most extreme case of image and text relationship (Kurwinkel 2017: 164).

“This Is Not My Hat” is full of “Contrapuntal tension”. As the text follows the small fish’s thoughts the images tell viewers just how much he’s mistaken. While a few passages don’t follow this structure it does dominate the way Jon Klassen tells the story. Those ongoing contradictions in information add to the ironic humour of the book. It is told from two perspectives at the same time: Assumption and truth.

What do we Learn?

There are complex structures on all levels of this picture book. The result might seem simple, but there’s more to the story than what can be seen at first glance. The characters themselves and their interactions can tell viewers quite a lot about human behaviour, socially and psychologically. The illustrations guide us through the story in a very thought-out manner despite being seemingly simple. And the interaction of text and images heightens the tension of the story, resulting in humour and insight about truth and assumptions.

This book probably won’t harm children, it would probably even be quite fun. It goes without saying that the story is harsh. Therefore, in order to get the most out of it, reading and discussing it together with the children can benefit all readers from all ages.

Sources

Art of the Picture Book (2014): An Interview With Jon Klassen. In: https://www.artofthepicturebook.com/-check-in-with/2014/10/15/interview-with-jon-klassen, accessed 02.12.2018

Hladíková, Hana (2014): Children’s Book Illustrations: Visual Language of Picture Books. In: Cavagnetto, Stefano (ed.) (2014): CRIS. Bulletin. Prague College Centre for Research & Interdisciplinary Studies. Prague: Prague College. 19-31. In: https://manualzz.com/doc/39054674/bulletin—prague-college, accessed 02.12.2018

Klassen, Jon (2012): This Is Not My Hat. Somerville: Candlewick Press.

Kurwinkel, Tobias (2017): Bilderbuchanalyse. Narrativik – Ästhetik – Didaktik. Tübingen: Narr Francke Attempto Verlag GmbH

Lanes, Selma (1980): The Art of Maurice Sendak. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

Thiele, Jens (20032): Das Bilderbuch: Ästhetik – Theorie – Analyse – Didaktik – Rezeption. Oldenburg: Isensee Verlag.

Von Klemperer, Caroline / Rodgers, Andy (2016): This is Not My Hat. In: https://www.teachingchildrenphilosophy.org/BookModule/ThisIsNotMyHat, accessed 02.12.2018